Gooseberry plants can be propagated easily by layering. I have layered plants successfully from fall until early spring. Shoots layered then will root by July and can be separated from the mother plant then.

After packing potting media around drain holes, a couple handfuls of soil will hold it in place.

Because field plants are growing in groundcover and not bare ground, I layer into 6” pots (trade gallons) filled with soil. A handful of potting media in the bottom keeps soil from washing through the drain holes when it rains; grass clippings also work.

Next bend the shoot into a U-shape as shown above, leaving the tip end exposed; and fill the pot with soil. Water if the soil is dry.

Typically I cut the layer free of the mother plant by July when our weather turns dry and normal rainfall cannot keep the soil in the pot moist.

I have used one-year and older shoots for layering. New shoots in midsummer are brittle and tend to break when bent into a U-shape.

In our climate I have not had success layering into potting media alone. It dries out between rains too fast to support rooting in the field. Roots will survive in soil even when it appears dry.

Layering this way also facilitates crossing as it is much easier to make crosses inside a greenhouse with potted plants than it is to make crosses in the field.

4-24-23 A shady location away from the edge of the row where equipment will not disturb the pots is ideal. This is R. missouriensis.

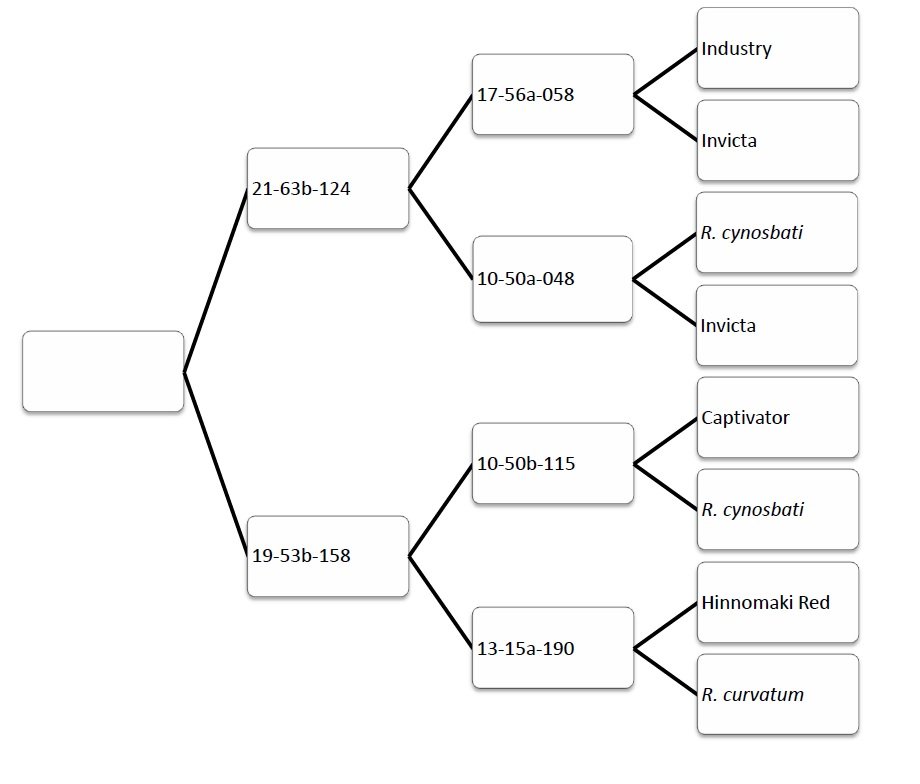

3-11-24 Spring growth on shoots of 10-50b-115 (Captivator x R. cynosbati) layered fall of 2023.